William Powell … Jamie Darricott

Kay Francis … Norma Page

Carole Lombard … Rachel Fendley

Gilbert Emery … Horace Fendley

Olive Tell … Mrs. Fendley

Martin Burton … Anthony Fendley

John Holland … Peyton Walden

Frank Atkinson … Valet

Maude Turner Gordon … Therese Blanton

Hooper Atchley … Headwaiter

Richard Cramer … Private detective (as Dick Cramer)

Edward Hearn … Maitre D’

Lothar Mendes … Lobby extra

William H. O’Brien … Elevator starter

Frank O’Connor … News clerk

Directed by Lothar Mendes.

From the Novel by Rupert Hughes.

Screenplay by Hermen J. Mankiewicz.

Sound Direction by Harry Lindgren.

Cinematography by Victor Milner.

Released April 30, 1931.

A Paramount Picture.

Background:

“I’m offering a direct challenge to the movie public, playing this part,” William Powell told reporters. “I’m throwing down the gauntlet. I am not a ladies’ man. I haven’t the physical characteristics, for one thing. I am not handsome. Someone like Valentino should have played this part, not Bill Powell.”

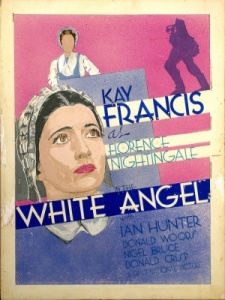

His complaints about Paramount’s casting of him in Ladies’ Man later echoed Kay’s own about her work in such films as The White Angel (1936), at Warner Brothers. Back then, when stars felt they got the raw end in a deal for a picture they wanted nothing to do with, they made their complaints known, and they were usually legit. But Roger Bryant, author of William Powell: The Life and Films, felt that Ladies’ Man was not worth Powell’s complaining, and that, if anything, it was worth a rediscovery.

Based off of a novel by Rupert Hughes, published in 1930, Paramount acquired the property for Paul Lukas and Kay, before replacing Lukas with Powell and throwing Powell’s then fiancé—Carole Lombard—into the mix. Hmm…the successfully established team of William Powell and Kay Francis going up against his new love-interest, Carole Lombard? Paramount must have thought they really had something here.

As a result, Ladies’ Man was given a first-rate production value.

Veteran Olive Tell was recruited to play the role of Mrs. Fendley. Her career had spanned fifteen years, beginning on the stage with Cousin Lucy (1915), and making her film debut in The Silent Master (1917), directed by French filmmaker Leonce Perret. Her role in Ladies’ Man would be an unsympathetic one, as Carole Lombard’s selfish and unrealistic mother, living in a fantasy world of materialistic value.

Her work in sound movies included The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929, with Norma Shearer) and Cock O’ the Walk (1930, with Joseph Schildkraut and Myrna Loy), until she ended her acting career in Paramount’s Zaza (1939, with Claudette Colbert). She died in 1951 of heart failure.

A veteran herself in a way, Carole Lombard had been doing bit parts in films since 1925, but Ladies’ Man proves she still had a lot to learn about screen acting. However, the film made her finally click with audiences. After this, she went on to starring roles in films like Virtue (1932), making her career stretch up until her tragic death ten years later.

And let us not forget, that it was Carole, who urged RKO to sign Kay for the third lead in In Name Only (1939), the film in which Kay made her big screen comeback after leaving Warner Brothers.

But if this film has any significance in the careers of any of its stars, it is Bill Powell’s. This was his last movie for Paramount before making his pit stop at Warner Brothers, before signing with MGM where he reached the peak of his popularity. Powell, Kay, and Ruth Chatterton were all recruited from Paramount to Warner Brothers with the promise of higher salaries, better scripts, and more publicity.

Interestingly, only one of those three would last, and that one would be the inspiration for this website, seventy-some years later.

Ladies’ Man opened to fair reviews, with most of the honors going to William Powell, though Time seemed convinced that this was Paramount’s chance at ruining his future with Warner Brothers (forcing him to play an unsympathetic lead). But audiences didn’t listen, and the Powell-Francis chemistry would shine brightest at Warner Brothers in One-Way Passage (1932).

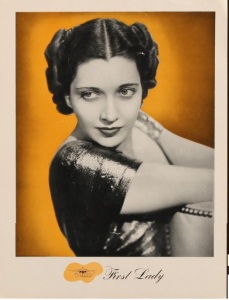

Above: From the April 1931 issue of Picture Play

Webmaster’s Review:

James Darricott makes a living off of dating older, well-married women who rank among the top of New York’s social class. For instance, he charms them, and they in turn make absolute fools of themselves, pawning everything they own to keep him around. But it is in Mrs. Horace Fendley where James as struck a gold mine.

Mrs. Fendley has two children, Anthony and Rachel. Both are aware that James accompanies Mrs. Fendley to parties and such when her husband is unavailable, but they are becoming more suspicious that there is more to their relationship than meets the eye. Matters are worsened when Rachel begins seeing James herself, causing a deserved frustrating resentment against her own mother, who is still very much married to Rachel’s father.

She asks James to give her mother up and settle for her, but James doesn’t love either one of them enough to do what’s best for them. Actually he doesn’t love anyone, except himself.

That is, until Norma Page comes along.

Rachel’s debutante party is attending by everyone of social importance in New York. Among the guests are Norma Page and her aunt. Norma is not from New York, staying only briefly with plans to return home the next day. She only sees James Darricott when she is leaving the party as he arrives. They meet in the doorway, stop, and she looks at him with a slight resentment, knowing exactly what kind of a man he is. He becomes in awe of her, and probably is more attracted to her distance towards him.

Not even sharing words, their relationship is established from here.

James meets Norma in a hotel lobby the next day, and asks her if he can show her around New York. She tells him that she needs to take the train to return home, but he gets her to stay in town just for one more day—or so he thinks. Later, when he goes to her hotel to pick her up, the manager informs James that Norma Page had already checked out.

Waiting at the train station, all of the passengers hop on board, and James assumes Norma is on the train, that he will never see her again. So isn’t he surprised when he turns around and there she is, all ready for a hot date with him and looking radiant in a beautiful evening gown.

The two run into Mrs. Fendley, who was told by James that he could not attend a dinner party with her because of his sick aunt, so she becomes insanely jealous of Norma, that she is able to possess James enough to take him away from her riches and money.

Leaving that location to avoid a scene, they go to a speakeasy where Rachel is emotionally devastated and drunk out of her mind. She’s in no condition to be out, so James and Norma take him back to James’ apartment where she can relax and sleep it off, and where Norma and James can continue their date by looking at the New York City skyline from his balcony. After Rachel wakes up she confronts James and tells him that she loves him, and that she will kill herself if he refuses to marry her.

Anthony shows up in the middle of her big scene, and takes her home. Oddly, none of this seems to bother Norma.

As maybe two weeks go by, Norma and James become serious with each other. Finally he has met a woman who he can honestly say he loves, and Rachel begins to awaken to her senses, and confides in her father that it was not just her mother’s heart whom James has captured, but also her own. Her father tries to tell her nothing is really going on between her mother and James, but she is not a child anymore, and he is unable to convince her.

Mr. Fendley didn’t mind when James was making a fool of his wife, because he knows exactly what his wife is, but because James has broken Rachel’s heart, Mr. Fendley decides it is time for revenge.

As Norma and James prepare their marriage plans, Mrs. Fendley arrives. Norma leaves after James confesses that he wants no more to do with her, and that he and Norma plan to be married. Mrs. Fendley does not take kindly to this, and tells James that if he marries Norma she will kill him. Just as she makes that announcement, Mr. Fendley walks in, and tells his wife to go to the party that is being held by her.

Mr. Fendley pulls out a gun, James flips the lights off, and there is a struggle. Two shots go off, and James pretends to have been shot, then he gets up and attacks Fendley, and the fight moves towards the balcony where James is flipped over.

Norma, just arriving to the hotel, throws herself over James’ body, while Mr. Fendley goes to the party where the police nab him.

As spectators gather around James and see Norma crying, one asks why she is so upset. “He loved me,” she says, teary eyed. “They can never take that away from me.”

This is one of the better movies Kay and William Powell made together, if not because of a stellar script, direction, or impressing lead performances, than because of the beautiful chemistry between Kay and William. The film is easy to follow, and moves quickly just as soon it as begins.

James Darricott is the stereotypical character fans remember William Powell best for: A debonair “ladies’ man” who is surrounded by the finest material objects money can afford. Though he is cold and unfeeling to the trashy snobs around him, it is the love a sympathetic socialite who saves him from self-destruction. In those days, Kay Francis was the definitive sympathetic leading lady who awakened Powell to true love and affection.

Her character is an interesting one. She knows exactly the kind of man Powell is, knows all the lines and tricks, but allows herself to fall for him away. Her hard-to-get approach is what traps him. After having everything he wants, he wants what he can not really have, and once he gets it, he comes to realize that he might not be deserving of it. Though she tells him that this is nonsense, that she will have her name dragged through the mud right beside his, a stronger fate saves her before it is too late.

In her emotional scenes at the end, Francis still shows us that she has a lot of learning to do. She’s too devastated, and clearly needed a few more movies before she was beautifully mannered down, grieving for Powell beautifully and flawlessly in One-Way Passage (1932).

Another one who needed more practice was Carole Lombard. Her drunk scenes are amateurish, and she delivers her lines with a coldness and is rather stiff in a lot of her scenes. At the speakeasy, she is overly sloppy, though her bad performance is not one to be singled out. This was typical for many of the younger actresses of this era.

Olive Tell is in good form as the pathetic Mrs. Fendley, who would go to the most drastic measures to live the most unrealistic lie: That she is enough to make a young, attractive man love her for who she really is. Tell plays Mrs. Fendley as a selfish, materialistic bitch, which is how it should be. Her unappealing photography only strengthens one’s disgust towards her character.

It would be interesting to note that Tell was only eleven years older than Kay in real life, and fourteen than Lombard, though she plays Carole’s mother.

Ironically, though they were engaged through the filming, there is little chemistry between Carole Lombard and William Powell.

Today, Ladies’ Man can best be described as a “headline-getter.” It’s main cast of stars—Powell, Francis, and Lombard—are the only real appealing aspect of this title to people who know little about it. As moviegoers, we have a desire to watch major movie names play off of each other, and with classic movies, we have a desire to see stars with so little associated in their legacies in obscure movies that nobody knows about.

What else would make Reunion in France (1942), with Joan Crawford and John Wayne, worthy of a prestigious DVD release from Warner Home Video?

Ladies’ Man is a prime example of that. Powell is best known for his work with Myrna Loy. Lombard is best known for her marriage with Clark Gable. And Kay is best remembered, if at all, for her expensive wardrobe. So when people like myself find movies like this which tie Powell, Lombard, and Francis together, it adds something to this movie that makes it stand out. And when watching scenes in which the three of them were together, it makes me wish I was a fly on the wall, so I could see how they interacted with each other off stage.

But don’t get a desire for gossip right away, Francis, Lombard, and Powell were all part of the same circle of friends.

Vintage Reviews:

“Women are always waiting for some one—and Mr. Darricott comes along,” a character in “Ladies’ Man” remarks at one point. “If you don’t marry me, I’ll kill myself,” an inebriated young woman screams as she bursts into Mr. Darricott’s apartment along about 3 in the morning. “I trust dinner and the theatre will be just the beginning of the evening,” another young woman says brightly as she leaves the hotel on Mr. Darricott’s arm. And at the close, after Mr. Darricott has been slain by the irate husband of still another woman, his epitaph is spoken by the girl he had confessed to really loving. “He loved me,” she tells a policeman. “They can never take that from me.”

All of which gives an inkling of what to look for in the new entertainment at the Paramount. William Powell’s intelligent performance as the fashionable gigolo and some comparatively grown-up dialogue by Herman J. Mankiewicz save the picture from being a complete bore, but even at that it has its trying moments. Lothar Mendes, the director, has permitted too much idle chatter to creep into the microphone, and he has made a bad story worse by telling it with neither clarity nor distinction.

Mr. Darricott, it must be evident by this time, is a man with an irresistible attraction for women with busy husbands or dull escorts: He kisses hands exquisitely, and his voice, whatever he happens to be saying, has the quality of a caress. He lives, it appears, by selling the jewelry given him by his wealthy female friends.

All the trouble starts after Mr. Darricott becomes Interested in Mrs. Fendley, wife of a banker. Her daughter Rachel falls desperately in love with him, either to save her mother’s reputation or because she happens to be a young and very foolish girl. The film does not make this point clear. Adding fuel to the flames, Mr. Darricott himself becomes enamored of another woman and makes a sincere effort to live decently for her sake. But the angry banker spoils everything by tossing Mr. Darricott fifteen or twenty stories into the street from his apartment.

Mr. Powell receives capable support from the others in the east, Kay Francis appears as the girl he loves, Carole Lombard is Rachel Fendley, Olive Tell is Mrs. Fendley and Gilbert Emery is the outraged banker-husband-father.

A pertinent comment on “Ladies’ Man” was delivered by a young man sitting behind this observer at yesterday’s early showing. “It seems pretty good,” said the young man, “but I can’t make out what it’s all about.”

Published in the New York Times, May 1, 1931.

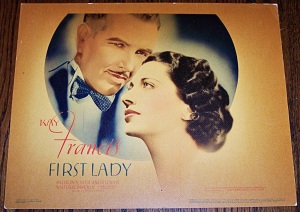

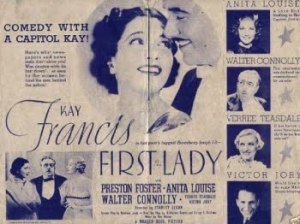

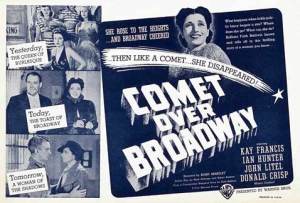

Film Advertisements

A

A