Ronald Colman … Jim Warlock

Kay Francis … Clemency Warlock

Phyllis Barry … Doris Emily Lea

Henry Stephenson … John Tring

Viva Tattersall … Milly Miles

Florine McKinney … Garla

Clarissa Selwynne … Onslow

Paul Porcasi … Joseph, Maitre D’

George Kirby … Mr. Boots

Donald Stuart … Henry

Wilson Benge … Merton, Jim’s Valet

Halliwell Hobbes … Coroner at Inquest

Directed by King Vidor.

Produced by Samuel Goldwyn.

Screenplay by Frances Marion.

Original Music by Alfred Newman.

Cinematography by Ray June.

Film Editing by Hugh Bennett.

A Samuel Goldwyn Production.

A United Artists Release.

Released December 24, 1932.

Background:

After working successfully opposite Ronald Colman in Samuel Goldwyn’s production of Raffles (1930), Kay Francis was loaned out from Warner Brothers to United Artists for Goldwyn’s follow-up picture with the Colman/Francis teaming, Cynara (1932), one of the more interesting melodramas of the early 1930s.

Many authors have found parallels between Cynara and the Adrian Lyne’s classic, Fatal Attraction (1987), starring Michael Douglas, Glenn Close, and Anne Archer. In both, happily married men have extramarital affairs with women of mental instability. Cynara is modern in this fashion, but King Vidor’s direction of R. Gore-Brown’s “An Imperfect Lover” is different in tone and overall presentation of the subject matter at hand.

As mentioned, Cynara was based on Brown’s “An Imperfect Lover,” which had been turned into a London stage play by Brown and H.M. Harwood, and brought to the screen by Arthur Hornblow Jr., Myrna Loy’s future husband whom Kay later had an affair with herself. With a screenplay by Frances Marion, and a final production cost of $697,958, one would think that Cynara would rank a little higher up in popularity than it does. Yet, while some love this slow-moving melodrama, others can’t stand it.

Though Kay Francis is second-billed, she is seriously limited in her camera time. This is more of a showcase for Ronald Colman and Phyllis Barry, who made her film debut in Cynara. Having an uncanny resemblance to Kay, Barry’s career continued until the late 1940s, and most of her film work was in minor roles in small movies. It is perhaps her resemblance to Kay which limited her career in Hollywood. Knock-offs of big stars never quite turn out to achieve as much as the originals, but it is unfortunate since Barry shows us a great gift in her dramatic abilities as an actress. In styles and talent she varies between Kay and Ann Dvorak.

Slow-moving or not, Cynara was of major importance in the careers of both Ronald Colman and, in a way, Kay Francis. 1932 was Kay’s year to shine, perhaps the greatest she ever worked through. In that special year alone, she successfully switched studios, appeared in four of the most popular films of the year, and established herself as a star of major importance. She was no longer just an ordinary player in featured roles. Now Kay Francis had become one of the most watched and talked about stars in the entire movie industry, and her importance was represented in high box office grosses which were now topping that of Warner Brothers’ former female supreme, Ruth Chatterton.

But in her openly talked-about opinions, though, Kay Francis could honestly care less.

Webmaster’s Review:

The setting is Naples. Jim Warlock was a successful barrister whose career has been ruined following an affair with a tragic young woman while his wife was away on a holiday in Venice. He tells Clemency, his wife, that he has no other choice but to leave the country. He’s now a ruined man. She asks him exactly what happened between him and this young girl, and we’re taken to a flashback some months before.

Clemency is planning to leave Naples for Venice because her younger sister, Garla, has had some romantic mishaps. Clemency and Jim have an ideal marriage, one built on honesty, loyalty to one another, and trust. Jim doesn’t want her to leave, but she insists that she must, that her younger sister needs to get away from Naples, but not without supervision to find the same sort of trouble in another location.

That night, after Clemency and Garla have left, Jim goes out to dinner with John Tring, a sinister old man who has a reputation for being a womanizer in his past. At dinner, he tells Jim that “no woman is respectable unless she’s dead,” and then he takes Jim to the next table to sit next to two young woman, Doris Lea and Milly Miles, who live and work together.

Following dinner, the four go to see a movie, Charlie Chaplin’s A Dog’s Life, and when Jim takes Doris home, she gives him her full name, number, and where she works. On the drive home, John jokes with Jim about having a relationship with Doris while Clemency is away, though he dismisses this with the gesture of tearing up the paper Doris wrote her contact information on, and then throwing it out the window.

Jim takes the offer of judging a swim competition, one which Doris is in, and wins first place for thereafter. When she collects her prize, she falls and sprains her ankle, and Jim picks her up and takes her back to her apartment where the two sit beside the fire and become more acquainted.

Weeks pass, and Jim and Doris become seriously involved with each other, so much so that her distraction from her work has caused her boss to dismiss her services. The two take a holiday together, and come to the conclusion that they must get used to seeing less and less of each other because Clemency will be returning home in a few days. Though Doris agrees, she is just telling Jim what he wants to hear, and when Clemency does return, Doris even goes as far as to call on him at his house, where he urgently meets with her in person to tell her to back off.

He caves due to her heartbreaking sincerity over her love for him, and agrees to see her again.

In his office, he writes a lengthy letter to Doris, telling her that he has changed his mind, and that their relationship must end at once. When he gets home, Milly arrives to tell him off, that he has cause Doris to loose her job, that she has no where to go, and that Jim won’t even help to pick her pieces up and place them back together again. He agrees to write her off with a check—pay her off to stay away from him, but it’s too late. A policeman arrives at the door to say that Doris has committed suicide by poison, and that she was found with the letter from Jim at her side.

A trial follows, with Clemency learning of the entire affair. While on the stand, Jim, a true gentlemen, doesn’t answer if Doris had been involved with other married men. The truth is she had, and when the scene goes back to Naples Clemency asks Jim if there were. He tells her the truth, and then tells her goodbye.

Right after Jim leaves, John shows up and guilts Clemency into tracking Jim down. He tells her that, first of all, the whole thing was Doris’ fault, and then tells her that Jim might take his own life, and that it would be Clemency’s fault in a way.

She arrives at the dock, where she and Jim embrace one another, then wave goodbye to John from the ship.

Forget Henry Stephenson. Forget Viva Tattersall. Forget Florine McKinney. Hell, even forget about Kay Francis. This one is all about Ronald Colman and Phyllis Barry, both of whom are excellent in this one. The relationship between their characters is the center of this movie, and the entire production revolves around their involvement with one another.

Being a veteran performer, Ronald Colman averages well. He really doesn’t have a best scene, though the final one with him and Phyllis Barry on the bench is quite touching. He does, however, garner audience sympathy before, during, and after his adulterous affair. While not exactly going out for it, he plays Jim Warlock as a man who is just lonely. A man who doesn’t want his wife to leave, and takes an interest to a young girl who has a striking resemblance to her (Kay Francis and Phyllis Barry look almost identical). Their affair is completely innocent as a whole without being childish.

There is a lot more to their relationship than sex. That’s what makes Cynara different then the other films of the time.

Phyllis Barry, who made her film debut in this one, comes across as mature of an actress who had been working in films for five or six years. She’s exceptional here, and doesn’t give Doris a dim-witted mindset. She’s an emotional young girl, with no family, who turns to anything who can give her the love she has been looking for since she was a girl.

That’s the starter conversation when she and Jim are first introduced at the restaurant; that she has no one but Milly in her life.

Henry Stephenson, always the wiser-older man, here gives advice that would make any feminist track him down with a pair of scissors and seal his goodies in a pickle jar. He has no respect for women here, so don’t be expecting him to be as kind and generous as he is in Give Me Your Heart (1936) or Marie Antoinette (1938).

It is, however, an example of his “versatility.”

Limited in camera time, though not totally overshadowed by a stellar cast and story, is Kay Francis as Clemency. She doesn’t have much to do but wear some nice costumes and make strange facial gestures. But catch a glimpse of her face when the police officer arrives at the Warlock residence when the movie is ending. She’s got one noticeably scowling look on her face. It’s a look that stays embedded in one’s mind.

Though it runs a bit longer than it needs to, the film has beautiful production values and stunning outdoor scenes. It probably would be a little more interesting had they trimmed some minutes off of it, but it’s not a bad film at all, and unlike the other precode movies of its time, perhaps one of the more mature films of the era.

Cynara deals with scandalous actions, but it doesn’t intend to “shock” or “stifle” audiences. The film just intends to show mature content for adult audiences ready to see more than flashy sets and ridiculous circumstances.

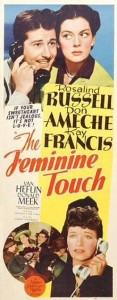

Film Advertisements:

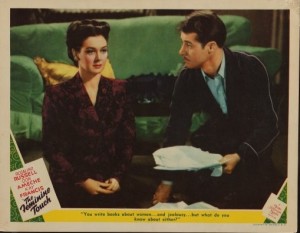

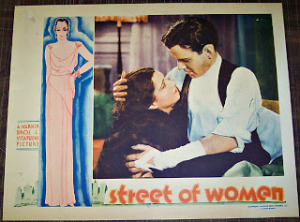

Original Lobby Card:

Original Herald:

Foreign Program:

Re-release Lobby Card:

Vintage Reviews:

Vintage Reviews: