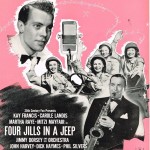

Cast:

Cast:

Kay Francis … Kay Francis

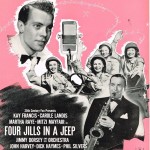

Carole Landis … Carole Landis

Martha Raye … Martha Raye

Mitzi Mayfair … Mitzi Mayfair

Jimmy Dorsey … Orchestra Leader

Jimmy Dorsey and His Orchestra

John Harvey … Ted Warren

Phil Silvers … Eddie

Dick Haymes … Lt. Dick Ryan

Alice Faye … Alice Faye

Betty Grable … Betty Grable

Carmen Miranda … Carmen Miranda

George Jessel … Master of Ceremonies

Produced by Irving Starr.

Directed by William A Seiter.

Story by Froma Sand & Fred Niblo, Jr.

Based on the actual experiences of Kay Francis, Carole Landis, Martha Raye & Mitzi Mayfair.

Music by Maurice De Packh, Jimmy McHugh, Harold Adamson, Leo Robin, Harry Warren.

Costumes by Yvonne Wood.

Make-up by Guy Pierce.

Set decoration by Thomas Little.

A Twentieth Century-Fox film.

Released April 6, 1944.

Box Office Information:

[The following appeared in the June 3, 1944 issue of the Motion Picture Herald. This figure does not provide the entire box office take for the film, only until the publication date of that specific periodical.]

Background Information:

Following some rumors in the press about a possible return to Warner Bros. as a contract star, and even having a few projects publicly announced by the studio, Kay Francis decided to place her priorities on the increasing war effort. She put her Hollywood career on the back burner, which was possibly the death knell for her stardom.

Not that her tours with the USO, Red Cross, and several patriotic causes were a character flaw by any means. Legendary Bob Hope later summed up her contributions perfectly: “Nowadays, people forget what a trouper Kay was. She did a lot for the USO and gave her time to many patriotic causes. She was a real class act.”

The problem with Four Jills in a Jeep, which was based off of a book by Carole Landis, is by the time it reached the screen it was completely altered from truth.

The original tour began on October 16, 1942 and ended a little over 3 months later. The tour included Great Britain, Ireland, and North Africa. The peak of the tour was when they performed for the Queen of England, which wasn’t shown in the actual film but, in the movie, the girls do put on a show for very upper crust London citizens.

Carole Landis did marry an officer while on the tour, but it ended quickly after the release of the movie. The sweaters that Kay, Mitzi Mayfair, Carole Landis, and Martha Raye wore were considered too revealing for the censors, and they were not allowed to wear them on the film. Little bits of information were modified to fit into a nicely idealistic film for wartime audiences.

Also, the women in real life had simply just asked to go, waiting for months for permission. In the film they go almost reluctantly. This kind-of changes the entire spark behind the whole thing. It makes them look as though they just got themselves into a mess of trouble when, in reality, they had their brave faces on and wanted to get as close to the action as possible without becoming a distraction.

This was the first USO tour for Martha Raye, who went on to do several more tours for other wars and earned a Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 1969 for her patriotic contributions. In conjunction with the release of Four Jills in a Jeep, she would appear in a small role in Pin Up Girl, which starred Betty Grable, who also had appeared in Four Jills.

Mitiz Mayfair had only appeared in short films and Paramount on Parade, which also boasted Kay Francis’ only appearance in Technicolor. Carole Landis’ life was cut short when she committed suicide.

Surprisingly, Kay Francis made no mention of it in her diary.

Aside from Grable’s appearance in the film, Alice Faye and Carmen Miranda also made cameo appearances as themselves. Unfortunately for Kay Francis fans, this was mostly done to beef up box office. None of the headlining stars had the draw to provide a financial return to match the extravagant costs.

From all the World War II and patriotic pride aside, for fans of Kay Francis Four Jills in a Jeep marked the finish line of her Hollywood and her stardom. While it’s nice to see she was still the center of attraction in a big movie after several years of supporting freelance roles, it wasn’t a very good production.

After this Kay Francis completed only 3 more films, all for the low-ranking studio, Monogram Pictures.

Webmaster’s Review

Four Jills in a Jeep opens up with Kay hosting a Command Performance over the radio. Betty Grable gets up and sings at the microphone. After Grable’s performance, Kay is joined by Carole Landis, Mitzi Mayfair, and Martha Raye to wish all the soldiers luck and give thanks for their efforts.

Backstage Carole, Mitzi, and Martha express their interest in taking the show abroad for the troops. Kay joins in to tell them that… surprise! She’s already off to England, and that they are welcome to come with her. The girls, a bit nervous, realize they have to go, realizing that their fears are minimum to the fears of the young men in active duty.

After arriving in England, they become acquainted with their tour guide, Eddie (played by the always obnoxious Phil Silvers). They meet up with the service men, and Carole begins to develop feelings for Ted, who helps her get out of the mud when she becomes unsurprisingly stuck as he looks on.

From the obscure base they make their way to London, where they put on a grand show for a bunch of upper-level civilians. Kay, beautifully dressed in a white evening gown with a head wrap, tells them that they have to sit on the floor “just like the boys do” when they put on their shows for servicemen. Martha Raye makes an idiot of herself singing and playing the piano, while Mitzi Mayfair does a dance which showcases her beautiful legs that help distract from her lackluster dancing skills.

Some romantic fluff begins to ensue, and Carole marries Ted.

From London they make their way to North Africa where they are met with skepticism. The female on the staff complains that they are in need of actual nurses not “you screen queens.” To her surprise, Kay helps the other girls roll up their sleeves and get their hands to work. When a doctor orders Kay (whom he does not recognize) to scrub the floors, she begins to do so. He realizes that it’s Kay Francis on her knees with a pale and brush and tells her she doesn’t have to. She continues anyway, and tells him to just refer to her as Kay. Not “Miss Francis or “Miss Kay.” “Please, just call me Kay,” she requests.

They put on a show for the men at the base and watch as they drive off on their next mission.

In all, it was very admirable what Kay, Mitzi, Martha, and Carole did. Actually, it’s very admirable what all of the Hollywood community did for the war efforts. But these were four of the stars who really got into the action and risked their own lives to help entertain the men who were protecting theirs.

The fault with this movie, and all of these World War II studios revues, is they’re just empty showcases for their current roster of stars. The actual final presentation of Four Jills, or even Thank Your Lucky Stars or Hollywood Canteen, is no different than the presentation that the studios were putting out 15 years earlier with the musical reviews when sound films came in.

For me, the only difference between Four Jills and Hollywood Canteen from Paramount on Parade and the Hollywood Revue is just that there are no two-strip Technicolor scenes and a war is involved. That’s all. But I would definitely consider Four Jills to be the most entertaining of the war musicals put out. The story here is much more interesting to follow than Hollywood Canteen or Thank Your Lucky Stars.

(“Much more interesting” as in watching sand fall through an hour glass versus watching paint dry.)

What’s nice about this film, as a Kay Francis fan, is it shows how she could still hold her own and headline the entire thing at 39 years old. When she’s in the field she’s in standard uniform, but in the beginning of the movie and in the London scenes, she is breathtakingly beautiful. She outshines Mayfair, Raye, and even Landis as the most glamorous member of the entire bunch. Even in their first night in England, she wears clothes to bed that are more beautiful than the average person would have worn to an upscale restaurant.

Viewers clearly expected Kay Francis to be a glamorous woman even 6 years after leaving Warner Bros. and just months shy away from turning 40 years old. And of that expectation, Twentieth Century-Fox clearly delivered.

Martha Raye does have some good comedy lines. Landis has a few heartwarming scenes as a young woman in love, but Mayfair certain just blends into the background. This is really a showcase for Kay Francis, and I’m not just saying that as a fan. She’s clearly leading the girls through everything, and she gets the most attention from the camera than any other star in the film. And it’s just so fascinating to see Kay Francis play Kay Francis.

Betty Grable, Alice Faye, and Carmen Miranda just make brief appearances that were inserted clearly to beef up box office. This definitely wasn’t a cheap movie to make, and, to be realistic, none of the feminine stars in the film had the draw to guarantee a return in profits. As a result, the most popular stars at Fox were just tossed in to lure more viewers.

Phil Silvers is the most annoying of the whole cast. His only shining moment is when he’s exchanging sarcastic words with a serviceman who says, “That joke’s my father’s.” Silvers responds, “And what are you, one of your mothers?”

That’s his only pleasant moment in the entire movie.

My personal opinions aside, there are many out there who love this film. Unfortunately, I’m one of the few who don’t.

This is one of Kay’s most popular films, but’s definitely far from her best.

Bosely Crowther review in the New York Times, April 6, 1944.

The adventures of Kay Francis, Carole Landis, Martha Raye and Mitzi Mayfair on a USD Camp tour of England and North Africa a little more than a year ago were no doubt diverting to the ladies. And the soldiers whom they entertained were probably so fired with admiration that we herewith proceed at our own peril. But it has to be stated bluntly that the film which Twentieth Century-Fox has made about that star-spangled journey among warriors is something less than okay. “Four Jills in a Jeep,” the claptrap saga which came to the Roxy yesterday, is just a raw piece of capitalization upon a widely publicized affair.

As an authentic record of that journey it may or may not have its points. Miss Landis meets a flier in this picture and marries him, as she did on the tour. Miss Mayfair casts dream eyes at a soldier who does a lot of singing in the film; and Miss Francis and Miss Raye have soulful moments with a medical officer and a clown sergeant, respectively. These latter romantic diversions may be accurate. We wouldn’t know.

But as a piece of screen entertainment it is decidedly impromptu. It gives the painful impression of having been tossed together in a couple of hours. All that happens, really, is a lot of dizzying about the dames and some singing and dancing by them in an undistinguished style. At a party in a London mansion (attended mainly by swells), Miss Raye sings “Mr. Paganinni” and Miss Mayfair dances to Jimmy Dorsey’s band. And in an old barn somewhere in North Africa Miss Landis sings “Crazy Me.” (This latter bit, incidentally, is the only one which rings remotely true.)

Otherwise, Dick Haymes sings two numbers, Phil Silvers clowns around a bit and Mr. Dorsey’s musicians contribute some musical time. Also, by virtue of the radio, Carmen Miranda, Betty Grable and Alice Faye are pulled in to warble hit numbers from recent Twentieth Century-Fox films.

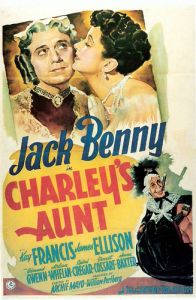

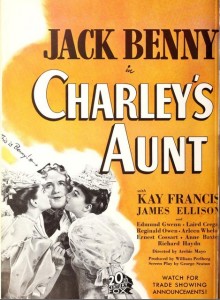

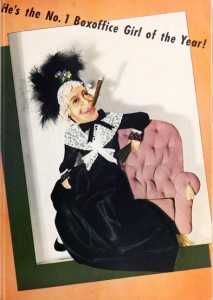

Film Images:

Film Advertisements

[Click image for a larger view!]

Original script for the film:

A Paramount Picture.

A Paramount Picture.