Cast:

Cast:

Kay Francis … Lucy Chase Wayne

Preston Foster … Stephen Wayne

Anita Louise … Emmy Page

Walter Connolly … Carter Hibbard

Verree Teasdale … Irene Hibbard

Victor Jory … Senator Gordon Keane

Marjorie Rambeau … Belle Hardwick

Marjorie Gateson … Sophy Prescott

Louise Fazenda … Mrs. Lavinia Mae Creevey

Henry O’Neill … Judge George Mason

Grant Mitchell … Ellsworth T. Banning

Eric Stanley … Senator Tom Hardwicke

Lucile Gleason … Mrs. Mary Ives (as Lucille Gleason)

Sara Haden … Mrs. Mason

Harry Davenport … Charles

Directed by Stanley Logan.

Produced by Jack L. Warner & Hal B. Wallis.

Based on the play by George S. Kaufman.

Screenplay by Rowland Leigh.

Art Direction by Max Parker.

Musical Direction by Leo F. Forbstein.

Musical Composition by Max Steiner.

Gowns by Orry-Kelly.

Cinematography by Sid Hickox.

Film Editing by Ralph Dawson.

A Warner Bros. Picture.

Released December 23, 1937.

Box Office Information:

Cost of Production: $485,000

Domestic Gross: $322,000

Foreign Gross: $102,000

Total Gross: $424,000 (Ouch!)

Please see the Box Office Page for more info.

Background:

For his lavish production of Romeo and Juliet (1936), producer Irving Thalberg had difficulty trying to find a leading Romeo to play opposite his wife’s, Norma Shearer‘s, Juliet. After Fredric March and Brian Aherne both walked off the project, Thalberg contacted Leslie Howard, Shearer’s costar in Smilin’ Through (1932), one of her most successful films.

Jack and Harry Warner agreed to loan out Howard, on one exception, however—that Thalberg loan out Norma Shearer to Warner Brothers in return.

George S. Kaufman’s First Lady had been a major hit on the Broadway stage with Jane Cowl in the Lucy Chase Wayne role. When Warner Brothers purchased the property in late 1936/early ‘37, it was designated to be Norma Shearer’s third film for Warner Brothers—she had completed two silents for the studio, Lucretia Lombard (1923) and Broadway After Dark (1924).

But Shearer turned down the opportunity to star in First Lady, and never completed her obligation for a loan out to Warner Brothers. After Romeo and Juliet, she completed only six more movies—all for MGM—one of which was the colossal Marie Antoinette (1938).

For box office security, considering how much money was going to be spent on First Lady’s production, Warner Brothers chose their top female star, Kay Francis, who had just been voted the sixth most popular female star in the entire movie industry by Variety. Preston Foster was the chosen leading man, and Verree Teasdale was selected to play Kay’s on-screen rival, Irene Hibbard (they should have chose Bette Davis, though Kay and Bette weren’t rivals, it would have made a much more intriguing film).

Kay was coming off a stellar box-office winning streak when First Lady went before the cameras in the summer of 1937. After ending 1936 on a high with Give Me Your Heart, Kay’s 1937 releases—Stolen Holiday (issues in February), Another Dawn (June), and Confession (August)—only topped her success in ticket sales. She was at the height of her movie stardom, and had earned the power to demand a real departure with First Lady’s production output.

First of all, she insisted that Orry-Kelly tone down the glamorous wardrobe, and instead gown her in more smart, modest clothing, fitting of what a Washington wife would wear. Second, she wanted the comedy to be brisk, sharp, and fitting to what higher social classes would find amusing. She was playing the wife of the Secretary of State, not the girlfriend of a construction supervisor over-seeing the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge (as she had in 1935’s Stranded).

While she wanted to mock the lifestyles of the snobbish politically-appointed employees who get into office solely by economical gain rather than hard work, Kay wanted it to be done in such a fashion where the honesty of their actions and values was the principle for the picture. First Lady was a comedy of truths, not fictions.

On the surface, this would appear to be why the film didn’t click. But analyzing First Lady on a closer scale reveals a bigger problem with the production which ultimately brought down the film, and the career of Kay Francis…

Stanley Logan made his film directorial debut with First Lady, which comes across as too-obvious. After a few reels, one doesn’t feel like he or she is watching a movie, but rather a stage play which has just been acted out in front of a stationary camera.

There aren’t many close-ups, or intriguing shots. The cinematography is cumbersome, and all we see are long shots of the entire cast playing out their scenes without any spontaneity.

It’s dead, and critics and audiences were largely unhappy with the film and Kay Francis, and she elaborated in an interview:

“The fans expect sincerity from me, a certain warmth and ‘sympatica.’ And if they don’t get it they howl. They didn’t like me in First Lady worth a cent. They told me so, by the hundreds.”

First Lady was the box office failure which ended Kay’s days as a reigning screen queen. Bored with the melodrama of Confession and Stolen Holiday, Kay demanded a change from Jack Warner, and insisted on being cast in First Lady. When the film failed, both felt the sting.

By the time First Lady completed its theatrical run, a major change was happening on the Warner Brothers lot, one which would hamper Kay’s career severely. She filed a law suit against the studio on September 4, 1937, and began the infamous “battle of the twentieth century.”

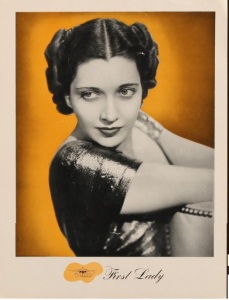

Above: A spread from the November 1937 issue of Picture Play.

Above: A spread from the November 1937 issue of Picture Play.

Webmaster’s Review

Lucy Chase Wayne is the granddaughter of former President Andrew Chase, which gives her a social standing in the Washington, D.C. circle. However, she is the wife of Secretary of State Stephen Wayne and insists that he has the presidential potential to succeed in the Oval Office. It is this, and her desire to earn the First Lady title, which are the main aspects of this movie.

Standing in Lucy’s way is Irene Hibbard, the wife of Carter Hibbard, one of the judges on the Supreme Court. Irene is another social climber, but one with an unfavorable past. She may not have been a lady of the streets, but she came from a lower-class, and first made herself important by marrying a “prince” Gregoravich, who turned out to be the heir to absolutely nothing after the First World War. It is because of this she left him and got with Carter, whom she finds dull and annoying.

Getting restless and irritated by her husband’s dull lifestyle, Irene decides that it is time for them to be divorced, that is until some of the Senators suggest that he has the presidential appeal to him which might win Irene the First Lady title for herself.

It is here where the story slightly picks up.

Lucy throws a dinner party to celebrate Carter’s decision to run for Office. On the phone with Stephen, she hears that Stephen has some work to finish with Gregoravich, and insists that Stephen bring him back to the house so Stephen can attend the dinner with their contemporaries. He does so, and while the others are in another room, Lucy silences Irene by introducing Gregoravich to her, in which he reveals the news that they are still technically married, which makes Irene’s marriage with Carter unofficial.

Because of this Carter is forced to resign from his campaign, allowing Stephen to move into his spot, which seems like a sure-fire win for everybody at the party.

Kay is upstaged by the majority of the cast, especially Verree Teasdale as Irene Hibbard, Walter Connolly as Carter Hibbard, and Marjorie Gateson as Sophie Prescott. The problem with Lucy Chase Wayne is that she is a character without range and depth. The lack of story and poor direction don’t help the situation either. Perhaps an actress like Katharine Hepburn or maybe Irene Dunne could have done a little better with the part.

Her best scene is after the small dinner party to celebrate Carter’s decision to run for President, in which she and Irene go about politely insulting each other, with Lucy winning the battle by brining Gregoravich to the house to meet with Irene. This is a pretty good scene, but again Teasdale succeeds at taking the audience’s attention and favor.

On top of things, Kay doesn’t have great chemistry with Preston Foster, though he does good in his part. The two are believable as a married couple, but couple married on a social status, not because of love and emotional attachment, which is supposed to be the real aspect of their life together which separates them from the rest of Washington, D.C.

There are two big scenes between Verree Teasdale and Walter Connolly in the Hibbard’s drawing room which stand out above the rest, though both are a little exaggerated and could have been cut down by several minutes. Connolly was a wonderful character actor, and it is his work as obese and sickly men like Carter Hibbard which won him favor with the audiences of the time.

This film should have been about Verree Teasdale’s Irene Hibbard. She’s a perfect snob; pretentious, uppity, and a projection of false values and what not to achieve. Irene Hibbard is a social climber who married for position, something Lucy Chase Wayne chose not to do.

Louise Fazenda is annoying as Mrs. Lavinia Mae Creevey, which is how she should be.

The poor story material doesn’t help this film at all. This is a perfect example on how Hollywood could ruin even the best of stage plays. It was horribly adapted to the screen, and Warner Brothers should have chosen a director with more experience to work on such a prestigious film.

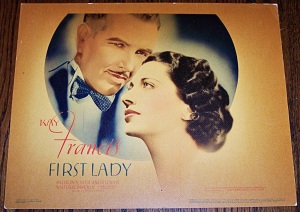

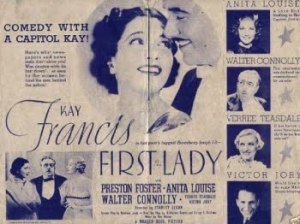

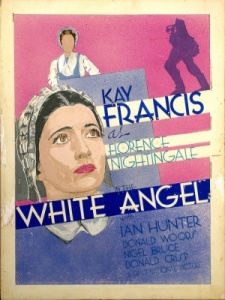

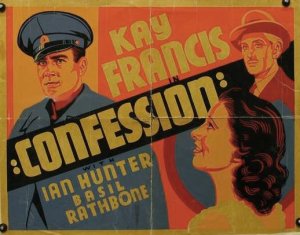

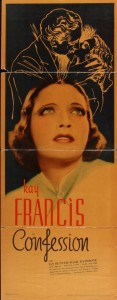

Film Advertisements

Movie Herald:

Misc. Images:

From the November 1937 issue of Photoplay

Review from Screenland Magazine, December 1937