Cast:

Cast:

Brian Aherne … John Evans / Malcolm Scott

Kay Francis … Adrienne Scott

Henry Stephenson … Frederick Collins

S.Z. Sakall … Paul

Nils Asther … Peter Ransome

Sig Ruman … Dr. Simms

Dorothy Tree … Mrs. Van Avery

Janet Beecher … Mrs. Milford

Marc Lawrence … Frank DeSoto

Henry Kolker … Mulhausen

Sarah Padden … Maid

Eden Gray … Venetia Scott

Selmer Jackson … Mr. Green

William Gould … Mr. Ryan

Russell Hicks … Mr. Van der Girt

Frederick Burton … Mr. Milford

Margaret Armstrong … Mrs. Van der Girt

Directed by Edward Ludwig.

Produced by Lawrence W. Fox.

Based on the novel by H. De Vere Stacpoole.

Screenplay by Eddie Moran.

Original Music by Hans J. Salter.

Cinematography by Victor Milner.

Film Editing by Milton Carruth.

Art Direction by Jack Otterson.

Set Decoration by Russell A. Gausman.

Gowns by Vera West.

Special Effects by John P. Fulton

Released March 21, 1941.

A Universal Picture.

Background:

In the year The Man Who Lost Himself was made, the year America entered World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, Kay Francis made four forgettable comedies. This was the only year in her entire Hollywood career where she did not make one dramatic film.

In some ways it’s good. In other ways, it’s not.

Kay started the year off with Play Girl, made for RKO. It was a so-so film, floating between the low A and high B range in production value. After that she went on to this movie, then to a supporting role in Charley’s Aunt and then The Feminine Touch, with Rosalind Russell, Don Ameche, and Van Heflin.

While her talents for light comedy were fine, ably assisted by her charming smile and hearty laugh, it was in the heavy dramatic roles in which she really shined. This was something Warner Brothers picked up on, which is why she suffered on screen for so long before her roles finally began to lighten up a bit, causing a down-turn in her popularity.

Unfortunately, her popularity was still undecided by the movie studios by this time. After her contract at Warner Brothers ended it became clear Hollywood didn’t exactly know what to do with her talent.

By the time The Man Who Lost Himself went into production, she could care less about what the public wanted to see her in. As a freelancer, Kay had her pick of assignments, and picked as many good films and she did bad ones.

This advanced her career yet also damaged it. From now on, when a Kay Francis movie bombed at the box office, there was no guarantee that she would be given another chance to make up for it. So when her independent movies didn’t prove to be so hot, she began working as a leading lady supporting her male costar as actors like George Brent and Ian Hunter had done for her back in her Warners years.

The Man Who Lost Himself is a fine example of this.

Based off of a novel by Henry De Vere Stacpoole, The Man Who Lost Himself had been filmed previously in 1920 starring William Faversham and Hedda Hopper in the roles later taken on by Brian Aherne and Kay Francis. By 1940, after he had completed Gone with the Wind (1939), Leslie Howard picked up this assignment, planning on producing as well as starring in it. The war caused him to abandon the project, it was picked up as a vehicle for Cary Grant and Kay, though when the project landed at Universal Studios Cary was recast with Brian Aherne.

Aherne was a British stage actor who had begun his career at the age of eight. By the time he appeared in The Man Who Lost Himself he had worked with Joan Crawford in I Live My Life (1935), with Constance Bennett in Merrily We Live (1938), and Madeline Carroll in My Son, My Son (1940), a film which was originally conceived as a vehicle for Kay. The year he made The Man Who Lost Himself, he also appeared with Jeanette MacDonald in a Technicolor remake of Smilin’ Through.

He was one of the most popular actors of the time, and Kay’s equal billing to his name in the film credits as well as all advertising materials proves her own popular status as late as 1941, when she was reportedly “washed-up.”

Reviews for The Man Who Lost Himself were largely favorable without being too enthusiastic. Variety found it to be “neatly packaged farce amply fulfilling its aim of light and fluffy entertainment.” Today, it survives as an antique piece, something interesting only to those who have an eye for this kind of subject matter.

Webmaster’s Review:

Malcolm Scott has just escaped from a mental institution. Being a wealthy man, no reason is ever given on why he was in one, though everyone clearly dislikes him. He is in the middle of a divorce with his wife, Adrienne.

In a hotel bar, he runs into John Evans, a man who looks exactly like him though they have no relation whatsoever (of course). He also runs into Adrienne and her attorney, causing Malcolm to get into a heated discussion with the two, leading to his idea which is the concept of this film.

Malcolm gets John drunk and has him sent to his home. When John awakens in the morning, everyone assumes John is Malcolm, giving him the same icy receptions which reveal their huge dislike of the man everyone expect him to be.

One aspect of Malcolm’s life that John would like to get to know better is Adrienne, though she is obviously still resistant of him. She has a new boyfriend, Peter Ransome, and insists that Malcolm will never change. He tries to seduce her, giving her a passionate kiss that leaves her dazed and confused.

Unfortunately, word gets out that John Evans—in reality, it’s Malcolm who has taken John’s place—has been stuck by an automobile and killed. There is speculation to whether it was suicide or someone pushed him.

Meanwhile, Peter asks Adrienne if she is beginning to fall in love with her husband again. She doesn’t quite know, but tells Peter that they mustn’t see each other anymore (obviously, she’s back in love). Adrienne clearly makes up her mind a few minutes later, when she returns to the Scott house, drags John upstairs and begins to undress herself, causing John to up and leave the room immediately (if this was made ten years earlier, they would have slept together).

The family decides that Malcolm needs to be returned to the hospital, and, drugged up, John is placed in a straight jacket and taken away. Shortly after, Adrienne hears that her husband was the one who was killed, and rushes over to John to inform doctors that they have the wrong man.

Everything is cleared up, and John insists that everyone call him by his real name now, Mr. John Evans.

Adrienne slips herself into the straightjacket with John, announcing that “Soon I hope you’ll be able to call me Mrs. John Evans.”

Don’t expect another Strangers in Love (1932) with this film, but it really isn’t that bad of a movie, and certainly has its moments.

First of all, the situation is very ridiculous. These ones always are; the whole “unrelated look-a-like” thing was only done well in a handful of movies, most notably in Lady of the Night (1925) with Norma Shearer.

What makes this movie good is its cast. Brian Aherne, Kay Francis, and S.Z. Sakall equally share the honors here. Though Aherne has the dual role, Kay and Sakall do keep up with him ably, taking some of the scenes from the highly regarded British stage actor and upstaging him considerably.

For fans of Aherne, this role would most likely be a disappointment. He was so good in Juarez (1939), and it becomes clear that he is one of those talented actors who can’t make stale property come to life (which is the difference between an actor and a star). In his drunk scenes he is over the top, slurring his speech in an exaggerated manner and waving his arms up and down.

But one thing he does have is charm, and it rubs off considerably. One can see why Kay, as Adrienne, is so taken by him.

And while Aherne floats back and forth between lame and not-so-lame, Kay is better than she had been in years. In The Man Who Lost Himself she has come back to her famous onscreen glamour, gowned beautifully by Vera West in furs and evening gowns which are more memorable than the movie itself. She has one of the more attractive 1940s hairstyles, and is jeweled with pearl necklaces and large earrings.

She takes advantage of all of her scenes, being at her best when she reveals her sexual frustration for everyone to see. She makes no effort for subtlety. She’s a woman who knows what she wants..

While this is far from being a Meet John Doe (1941) or Ball of Fire (1943), certainly The Man Who Lost Himself deserves to be seen. Owned by Universal, it has become one of the more obscure titles of Kay and Brian Aherne’s respective careers.

Film Advertisements:

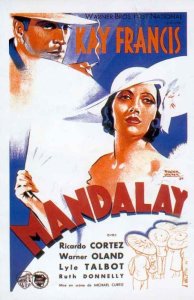

Posters:

Theater Slide: